A digital project named OnThisSpot has been launched, aimed at recounting the history of Canada’s First World War internment camps, including one in the Elk Valley.

The OnThisSpot app hosts the story of the Morrissey camp along with a number of other historical sites. The app allows users to take self-guided walking tours across places with historical significance.

When Canada enacted the War Measures Act during the First World War, thousands of Canadian residents were branded “enemy aliens” before being rounded up and sent to one of 24 internment camps across the country.

One such camp was built in Morrissey, an abandoned coal-mining town southwest of Fernie.

Canada’s move to take action against those coming from nations that it was at war with was broad and impacted a significant number of people across the country.

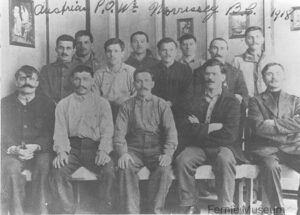

“There were 8,579 people who were interned, approximately 3,000 of those were actual prisoners of war and the remainder were civilians, and most were Ukrainian,” said Andrea Malysh, program manager of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund. “There were 17 other nationalities who were affected by World War I internment, and about 80,000 people had to register to the local authorities.”

Malysh said Germans, Austro-Hungarians, Ottomans, Bulgarians and a number of Jews were among those interred across Canada between 1914 and 1920.

Ironically, Malysh said many of those immigrants who were imprisoned were solicited to move to Canada’s western provinces to help bolster the workforce. Eastern Europeans, Ukrainians in particular, were drawn in with promises of free land in Canada, only to be interned when the war broke out.

According to Lindsay Vallance, Fernie Museum collections management coordinator, the camp in Morrissey was different than most others in Canada. Most camps were built in 1914, as part of the War Measures Act, but the one in the Elk Valley was constructed in 1915.

“Fernie’s camp was actually requested by some of the population of Fernie in 1915, and it was a provincial effort initially,” said Vallance.

“People who were called enemy aliens were reporting to the police constable every month in Fernie. If they were not naturalized citizens, they would have to report all of their information, they would be monitored and they would have to take an oath and they went about their business.”

Vallance said people who spoke out against the war were often sent to internment camps in Lethbridge or Vernon before the Morrissey camp was built.

Since Canada was at war with the Austro-Hungarian empire, Vallance said anti-Austrian sentiment was common. In early June 1915, mine workers and truck drivers in the Elk Valley went on strike, refusing to work with so-called “enemy aliens.”

They said they were worried that these enemy aliens would be saboteurs, and they would destroy the mine in some way or damage the workings of the mine,” explained Vallance.

The timing was also convenient for Elk Valley miners who were out of work.

“There was also an economic depression at the time, a lot of miners were unemployed and some that were employed were only working nine days a month. There were definitely economic reasons for them to be worried about other people having jobs at the mine,” said Vallance.

“If you put them all [European immigrants] in an internment camp, you wouldn’t have to worry about it anymore. There might have been patriotism, fear of sabotage, and maybe also they wanted their jobs.”

Mineworkers refused to work until military-aged German and Austrian men who were not yet Canadian citizens were imprisoned. This, according to Vallance, was one of the few circumstances where the union and coal mining company were on the same side, against the strike.

“They [mine workers] didn’t care if the immigrants were married or unmarried, they just wanted all of them out,” explained Vallance.

“The union was very surprised at this because the union wanted solidarity between all of the miners in its membership. It’s very difficult to have a union when one half of the union is trying to throw the other half in jail. The coal mining company didn’t want to get rid of a large portion of its workforce.”

Faced with the possibility of a riot should strike-breakers force miners back to work, the provincial government stepped in to establish an internment camp in Morrissey.

The issue, however, is that there was no internment camp built but the union and coal company wanted the workers back on the job. In the interim, over 300 men from the Elk Valley and other nearby communities, including Cranbrook, were confined to Fernie’s skating rink while a camp could be set up.

“While the prospect for them is not bright, most of them take the situation philosophically and are making themselves as comfortable and bearing themselves as cheerfully as possible. With music and games they are doing their best to forget their troubles,” said a passage from the June 11, 1915 edition of the Fernie Free Press.

Immigrants were housed at the skating rink from early June until October of 1915. On July 1, the federal government took over control of the camp and plans to establish a more permanent prison got underway. Morrissey was chosen as the site, as it was mostly abandoned by 1915.

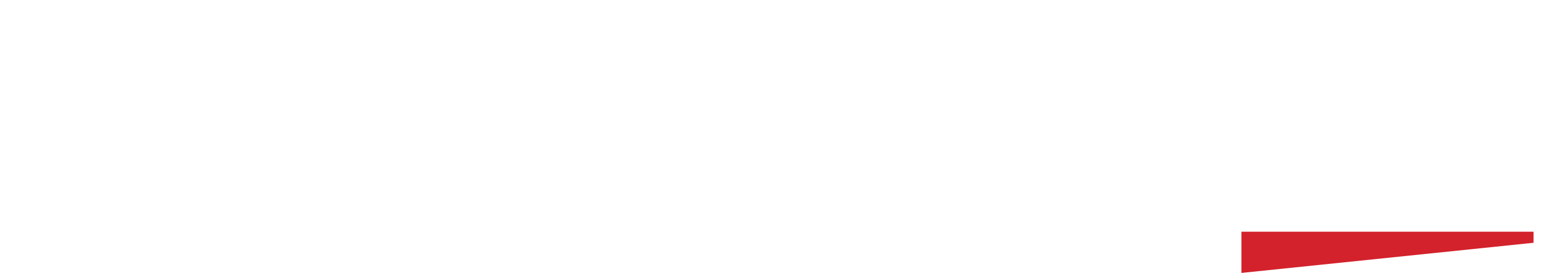

“It had been abandoned because the mines were too dangerous to work and they weren’t very productive,” said Vallance. “They had all of these big empty hotels and other buildings just standing there, so they decided that it would be a great place to put the internees.”

Despite being imprisoned, about 100 internees were sent back to work at the mines in October as production ramped up.

“Canada was at war and needed lots of steel, so that meant the unemployment rate was dropping and they needed them back,” said Vallance.

Many others were forced to work on various infrastructure projects in the region.

“They were used to help pave 2nd Avenue, they did work on the railway. They were paid a very low wage, and part of that wage would be taken out to pay for room and board and more was taken out to be put as savings for them, but of course, it wasn’t,” said Vallance.

German prisoners were paid 55 cents per eight-hour day – equivalent to about $13 in 2022, according to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator – while non-prison mine workers earned about $4 per day – about $100 in 2022.

Using prisoner labour was not unique to the Morrissey camp, however. According to Malysh, civilian prisoners were not governed under the Hague Convention treaties, and many of them were used as forced labour under the Canadian government.

“Parks Canada was built on the back of free labour. Out in Castle Mountain, Banff, Lake Louise, all the bridges and highways were built by internees,” said Malysh “A third of the camps ended up being in British Columbia, the government needed the free labour and they lacked the infrastructure.”

Malysh said Mount Revelstoke and Yoho national parks were also built using prison labour.

The Morrissey prison camp remained active until the end of the war in 1918, but several other camps remained open. According to Malysh, the last one closed in 1920, 18 months after Armistice.

“There’s much speculation as to why the camps stayed open,” said Malysh. “There was really no reason to keep them open past Armistice, and there was no reason to have these camps in the first place.”

Malysh said at least 107 people died while imprisoned in the internment camps and another 106 people went “mentally insane” following their release.

Many prisoners dealt with the lingering mental health impacts of being interred.

“It became a sort of crippling legacy that left these people traumatized for life. It affected their families and they were afraid of being interned again and afraid of the barbed wire fence,” said Malysh.

According to Malysh, efforts to get World War I internment camps recognized were challenging, as the Canadian government destroyed many records of the camps in 1954.

“When the Ukrainian community wanted to look at a redress settlement, the Canadian government told them to prove that it actually happened,” said Malysh. “This piece of history was buried, and I think the government wanted to bury it.”

Malysh said recognition of the World War I internment camps was partially thanks to Japanese Canadians seeking a settlement from their internment during World War II.

This article was written with contributions from the Fernie Museum and the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund. More on both organizations can be found below.

More: Fernie Museum’s Morrissey internment camp virtual exhibit

More: Fernie Museum website

More: Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund